Cartesian Poetics:

The Art of Thinking

René Descartes was not a poet. Of course he read poems, wrote many in school, quoted them in correspondence, possibly dreamt about them, maybe even wrote verses for a ballet, and knew friends of the censored poet Théophile de Viau. But proximity does not a poet make. That was fine; he had plenty of other things to do: finding a reliable method toward truth, taking down Aristotelians, developing a theory of optics, explaining rainbows. Yet poetry matters to Descartes and how we read his work nonetheless, and it matters because it makes some of his thinking happen.

Cartesian Poetics investigates the relationship between thinking and poetry in Descartes. It asks what thinking is good for, what it feels like, and what it defers, conceals, and exploits thanks to the abundant resources of poetic form. Locating in Descartes’s philosophy the incidental effects of his poetic education, centering the importance of literary critical interpretation with both its hazards and possibilities, this book understands thought to be vulnerable rather than impenetrable….

Articles and Chapters

2024

“Perrault’s Wager: Betting on Bluebeard and the Verse Epimythium,” Modern Philology

Poetry has some problems. Consider a few of them: it’s dying, it’s dead, and no one knows what it is. Counterintuitively, it suffers, like the rest of literature, from a great language deficit: in spite of the many words at literature’s disposal, “there is no word for a work of literary art.”

2024

“Descartes in Modern French Philosophy,” The Oxford Handbook of Modern French Philosophy

If ‘Descartes’ did not exist, he would have to be invented—if only for our convenience. For the seventeenth-century philosopher’s name has come to be the most economical signifier for the troubles of modern subjectivity and its alienations.

2023

“Another Report on Banality,” Crisis and Critique

My topic is banality in general and its usefulness for, and alongside, an interpretation of one comedy in particular: Beaumarchais’ The Marriage of Figaro. Comedy, however, is quite fairly not the first association to come to mind when it comes to banality.

2023

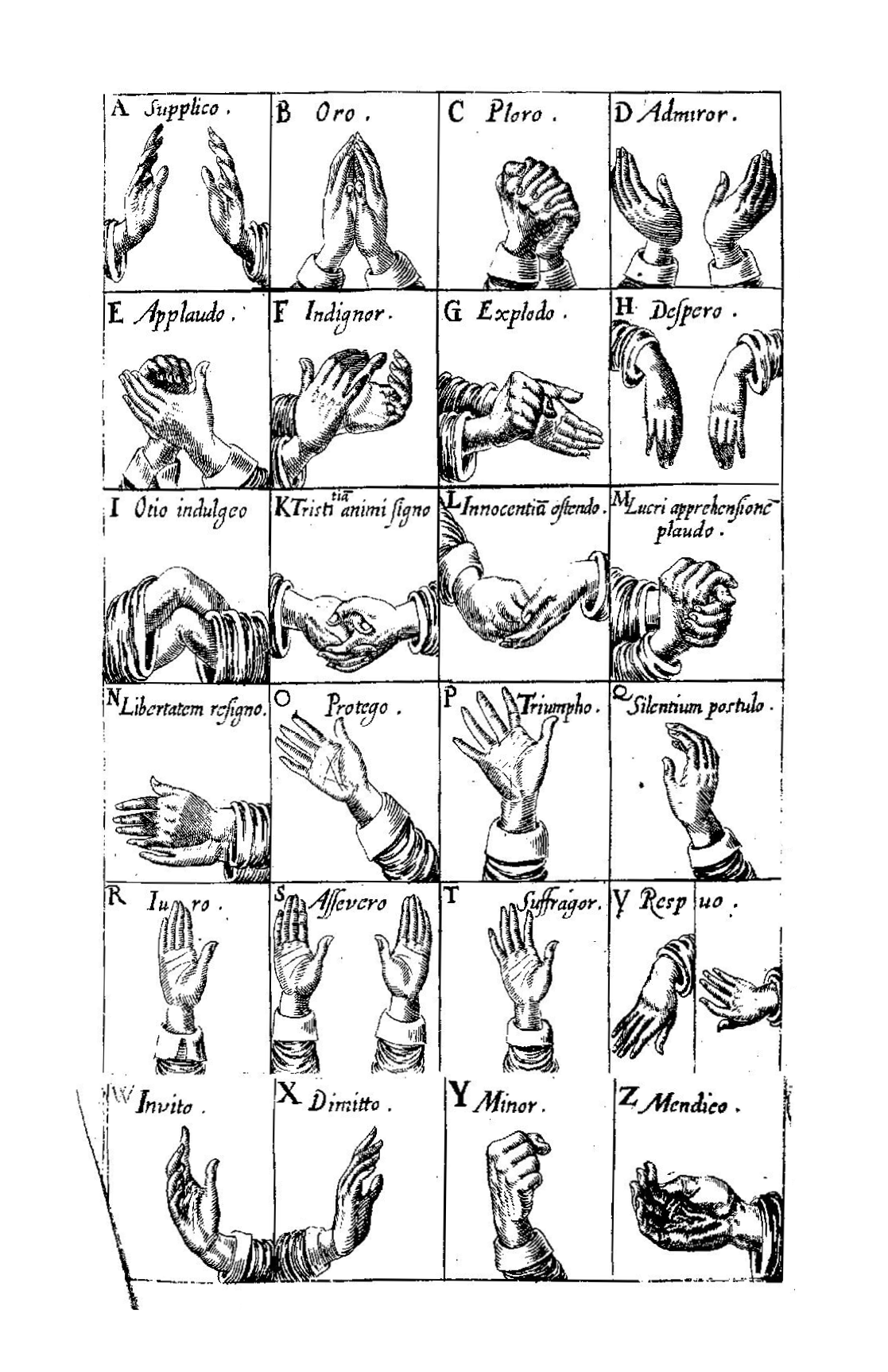

“Hand,” differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies

In The Culture of Redemption, Leo Bersani is missing a hand. The opening chapter, quoted above, invokes an “[o]n the one hand” without ever supplying “the other hand” to complete the locution in its most typical fashion. This is not a crime, and in mentioning it, I do not have in mind an editorial quibble, a bit of decades-late pedantry, or a complaint that I, too, did not receive from Bersani “the body I was promised.”

2022

“In Praise of Bog,” Crisis and Critique

In 1870, Emily Dickinson wrote a letter to her longtime interlocutor Thomas Wentworth Higginson telling him how she knew a poem when she saw one: “If I read a book and it makes me so cold no fire can ever warm me, I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only ways I know it. Is there another way?” Dickinson had read many poems, though, and by conventional accounts, her head seemed to be intact.

2021

“Night Thoughts: Am I dizzy, or am I dead?,” The Philosopher

Arguably, they were ideas meant to comfort. That it might be possible to prove one’s existence through the exuberant awareness of one’s own thought, that one could avoid nearly all errors by methodically snuffing out slovenly inferences in favour of the clear and distinct: these were among the contributions of Descartes, and their consolation did not so much conceal as overshadow what Descartes himself knew all along. Thinking could be a mess.

2021

“Thinking’s History: Descartes and the Past Tense of Thought,” Thought: A Philosophical History

This essay asks how Descartes understands thought – not in the pure present of its enunciation (in the instant of the “cogito”) – but when it is over and done with. The question I aim to answer here is straightforward: how is the “cogito” (“I think”) different from the “cogitavi” (“I thought”)? To rephrase my epigraph, my aim is to ask not “what thinking might be” but what it might have been.

2019

“What is the Second Estate?,” Telos

The aristocracy has long had at least one clarifying function: it delimits that which “the people” are not.

2017

“The Cupid and the Cogito: Cartesian Poetics,” Critical Inquiry

While the evil genius of René Descartes’s Meditations has never gone entirely out of fashion, perhaps no era before our own has been quite so hospitable to the malin génie’s project of duping the subject with systematic simulation.

Book Reviews

2021

Review essay on Hall Bjørnstad, The Dream of Absolutism: Louis XIV and the Logic of Modernity: (Chicago 2021).

2018

Review of Chenxi Tang, Imagining World Order: Literature and International Law in Early Modern Europe, 1500-1800 (Cornell 2018).

2015

Review of Hervé Baudry, Le Dos de ses livres: Descartes a-t-il lu Montaigne? (Honoré Champion 2015).

Works in Progress

Literature’s Cause

“The fact that everything which exists is caused should not only be thought of in the common way.” - Ernst Bloch, “Causality and Finality as Active, Objectifying Categories: Categories of Transmission”

“What has happened in poetry happens also in the philosophical world.” - G.W. Leibniz, letter to Clarke (1717)

Unlikely allies, Bloch and Heidegger agreed: when it came to talking about causality, something had happened between, roughly, the mid-seventeenth century and the mid-eighteenth. In truth, quite a lot had taken place: Aristotle’s causality was well on its way out, the “usurped concepts” (Kant) of fortune and fate seemed not to cede their seats so easily, and to top it off, there was a new language for grasping how one thing might lead to another, why things were the way they were, or how they might become so. Reading old mysteries of the will, desire, and fortune alongside their new formulations and emergent concepts like affinity, ground, and determination (old words that had taken on a new force), Literature’s Cause looks to works of early modern literature and early modern rationalism to inquire into causality’s literariness and literature’s cause(s).

Notes on Clapping

“Many things in the world have not been named; and many things, even if they have been named, have never been described.” – Susan Sontag, Notes on “Camp”

For all there is to say about handedness (whether “chiro-philosophy,” as Raymond Tallis would have it, or on “handicraft” as Heidegger would), about touch (for Jean-Luc Nancy, Derrida, and J. Hillis Miller as well as for Pablo Maurette, Daniel Heller-Roazen, Karen Barad, and others who have written on touch outer, inner, and impossible), about hands symbolic (the disembodied hands and dancing feet of Freud’s uncanny), spatial (as in Kant’s problem of “incongruent counterparts,” a topic treated by Wittgenstein, Moebius of strip fame, and also Deleuze), or digital, there seems to be nothing to say of the most banal achievements of any pair of hands: clapping. In Notes on Clapping, I aim to account for this silence and to show how this mundane gesture has been and might be grasped in language.